Behind every offshore wind farm is a complex, capital-intensive, and highly coordinated supply chain. While towering turbines spinning at sea often get the spotlight, the true backbone of offshore wind energy lies in manufacturing plants, ports, installation vessels, and global logistics networks working together with near-military precision.

As offshore wind projects scale up and move farther from shore, supply chain performance has become one of the most decisive factors influencing project cost, delivery speed, and investment risk. Understanding how this ecosystem functions explains why offshore wind is both expensive to build—and strategically vital to national energy security.

This article breaks down the offshore wind supply chain step by step, from turbine manufacturing to installation logistics, vessel fleets, and the emerging impact of floating offshore wind.

Table of Contents

Wind Turbine Manufacturing for Offshore Projects

Offshore wind turbines are fundamentally different from their onshore counterparts. They are larger, heavier, more powerful, and designed to operate continuously in harsh marine environments for 25–30 years.

Modern offshore turbines commonly exceed 12–15 MW per unit, with rotor diameters wider than football fields. Manufacturing these machines requires specialized facilities and highly controlled production processes.

Key Manufacturing Components

Blades

Offshore wind blades are among the largest composite structures ever produced, often exceeding 100 meters in length. Their scale improves energy capture at sea, where winds are stronger and more consistent, but creates major challenges for fabrication, transport, and handling.

Blade manufacturing relies on advanced composite materials, precision molds, and strict quality controls to prevent defects that could lead to catastrophic failure offshore.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) provides in-depth analysis of offshore turbine blade technology and materials science, highlighting durability and scaling challenges in marine environments.

Nacelles

The nacelle houses the generator, power electronics, gearbox (if used), cooling systems, and control hardware. Offshore nacelles are engineered with corrosion resistance, redundancy, and remote monitoring in mind, as maintenance access is costly and weather-dependent.

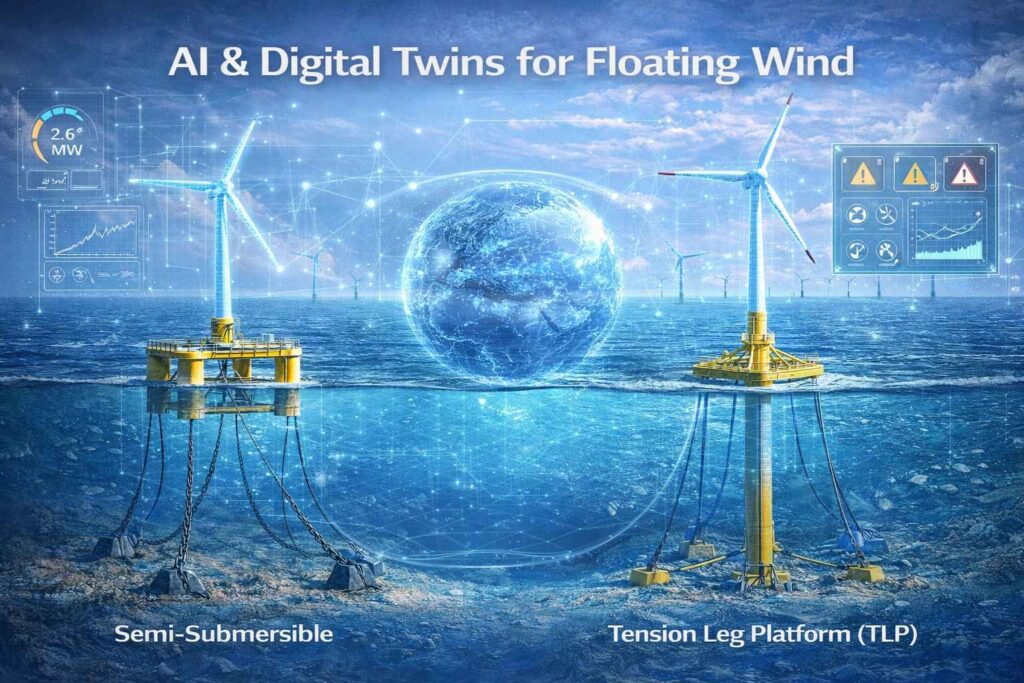

Many manufacturers now integrate digital condition monitoring and AI-based diagnostics to reduce downtime.

Towers and Foundations

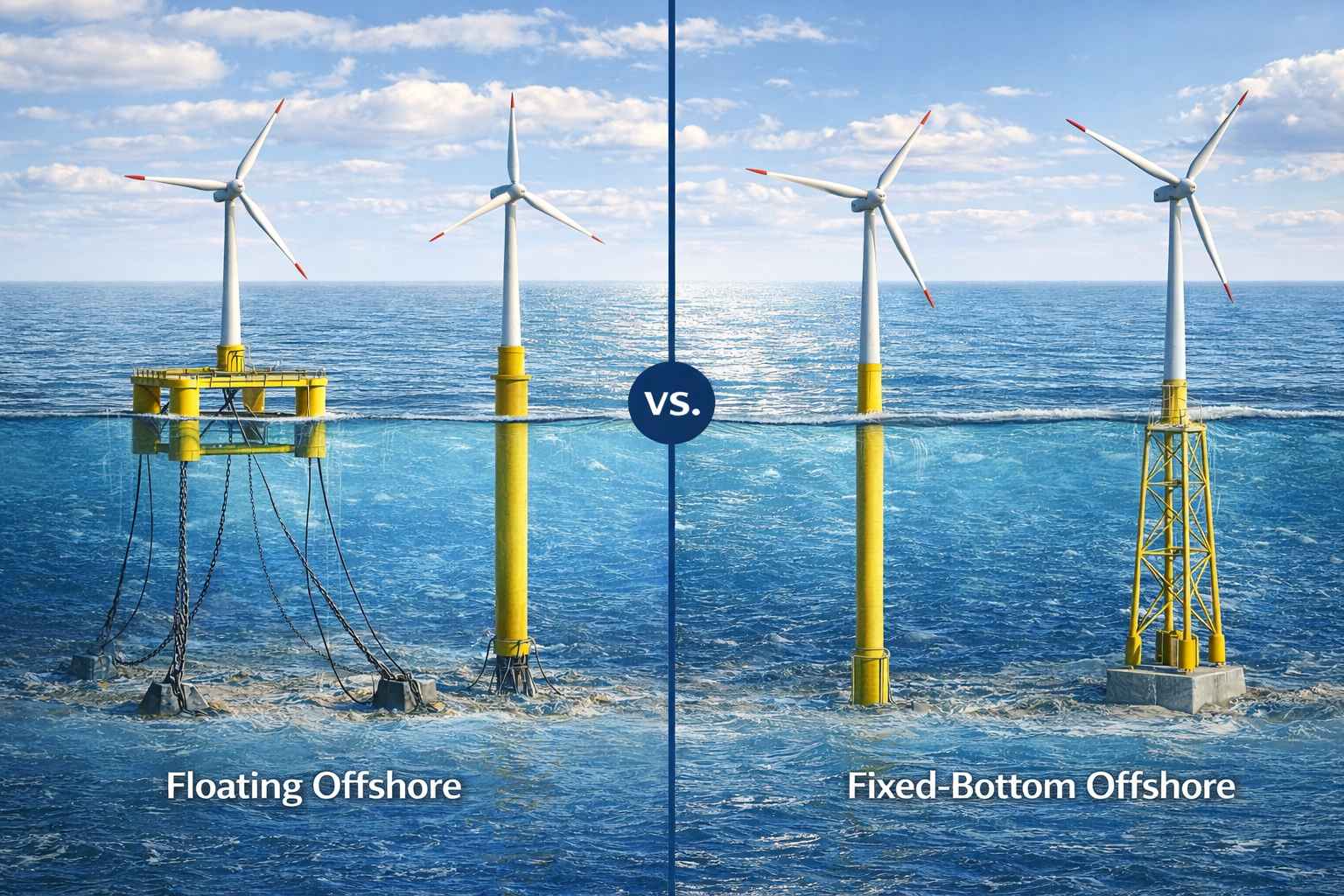

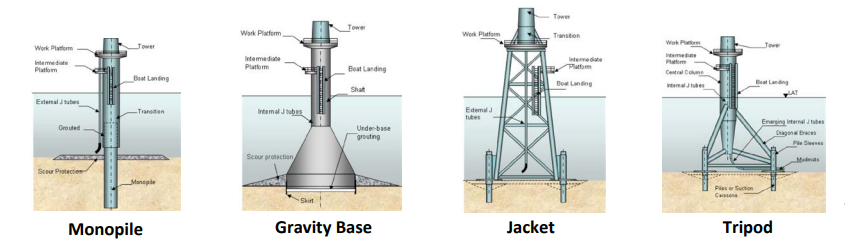

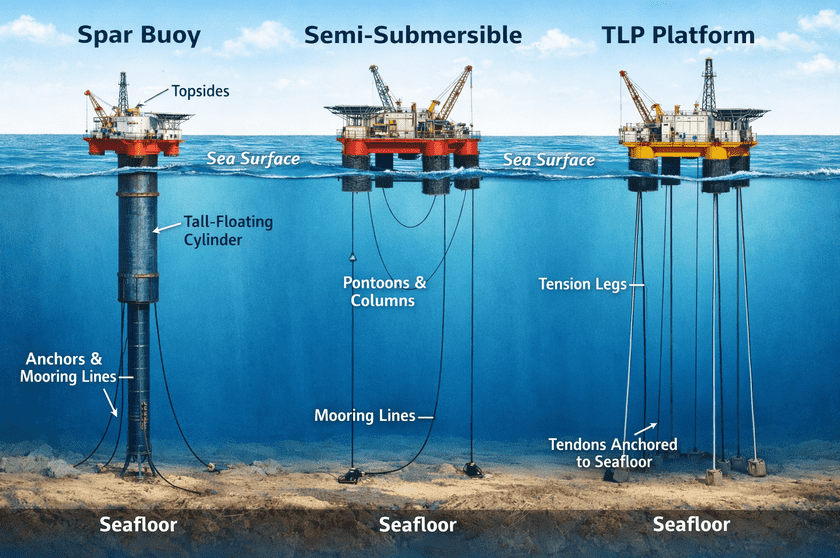

Offshore towers must withstand higher wind loads, wave action, and saltwater corrosion. Foundations vary based on water depth and seabed conditions and include monopiles, jackets, gravity-based structures, and floating platforms.

Manufacturing sites are increasingly located close to deep-water ports, reducing transportation complexity for oversized components.

Ports: The Hidden Hubs of Offshore Wind

Ports are the unsung heroes of offshore wind development. Without suitable port infrastructure, even the best-designed wind projects can stall.

Ports function as:

- Manufacturing interface points

- Storage and staging areas

- Pre-assembly hubs

- Launch locations for installation vessels

What Makes a Port Offshore-Wind Ready?

Modern offshore wind ports require:

- Deep-water access for heavy vessels

- Reinforced quays to support thousands of tons

- Large laydown areas for blades and towers

- Heavy-lift cranes and roll-on/roll-off capacity

Many countries are investing billions to upgrade ports specifically for offshore wind. WindEurope regularly tracks European port investment for offshore wind and explains why port readiness directly impacts project timelines.

Port capacity has become a strategic bottleneck, especially as turbine sizes continue to increase.

Offshore Wind Installation Process

Installing offshore wind turbines is one of the most complex construction operations in the energy sector. Every phase depends on weather windows, vessel availability, and precise scheduling.

Installation Stages

- Foundation installation – monopiles or jackets driven or placed into the seabed

- Subsea cable laying – inter-array and export cables installed and buried

- Tower installation – tower sections lifted and secured

- Nacelle installation – heavy-lift operation requiring calm seas

- Blade installation – either individual blades or pre-assembled rotors

- Grid connection and commissioning

Delays at any stage can cascade through the entire project timeline, increasing costs.

Specialized Vessels in Offshore Wind Logistics

The offshore wind supply chain depends on a fleet of highly specialized vessels, many of which are in short global supply.

Key Vessel Types

Jack-Up Installation Vessels

Used primarily in shallow waters, these vessels raise themselves above sea level using legs that rest on the seabed, providing a stable platform for heavy lifts.

Heavy-Lift Vessels

Capable of lifting thousands of tons, these vessels install foundations, nacelles, and large turbine components.

Cable-Laying Vessels

Equipped with dynamic positioning systems and subsea trenching tools, these ships install and bury power cables connecting turbines to offshore substations and onshore grids.

Tow-Out and Support Vessels

Used extensively in floating offshore wind, these vessels transport fully assembled platforms from port to site.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) highlights vessel shortages as a key risk to offshore wind deployment through 2030. Vessel availability has become one of the highest costs and scheduling risks in offshore wind projects globally.

Floating Offshore Wind and Supply Chain Evolution

Floating offshore wind represents a major shift in supply chain design.

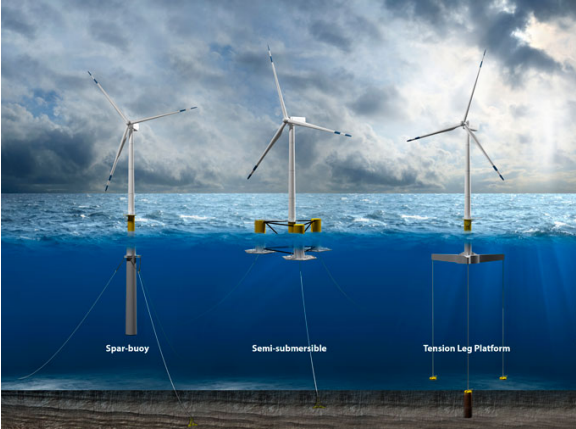

Unlike fixed-bottom turbines, floating systems are often:

- Fully assembled at port

- Launched and towed to the site

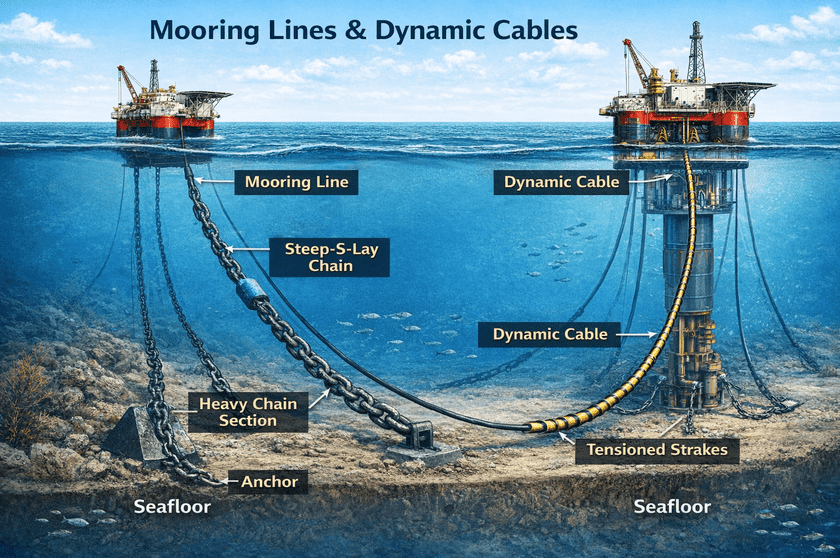

- Anchored using mooring lines and dynamic cables

How Floating Wind Changes the Supply Chain

Floating offshore wind:

- Reduces offshore construction complexity

- Moves more labor and value creation onshore

- Increases demand for large assembly ports and fabrication yards

- Expands offshore wind potential to deeper waters

The Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) explains how floating offshore wind unlocks new markets in the U.S., Asia, and Southern Europe.

As floating wind scales, ports may become even more central than installation vessels.

Supply Chain Challenges and Constraints

Despite rapid growth, offshore wind supply chains face serious constraints:

- Limited manufacturing capacity for large turbines

- Shortage of skilled labor and technicians

- Vessel bottlenecks and long lead times

- Port infrastructure limitations

- Rising steel, logistics, and financing costs

Governments and developers are increasingly adopting local content strategies to reduce risk, stabilize costs, and build domestic industries.

Why the Offshore Wind Supply Chain Matters

A resilient offshore wind supply chain:

- Reduces construction and financing risk

- Lowers long-term levelized cost of energy (LCOE)

- Speeds up project delivery

- Supports industrial growth and job creation

- Strengthens national energy security

Countries that invest early in offshore wind manufacturing, ports, and logistics gain a long-term competitive advantage beyond electricity generation.

Conclusion

The offshore wind supply chain is far more than a background operation—it is a highly technical, capital-intensive ecosystem that determines whether projects succeed or fail.

From turbine factories and reinforced ports to installation vessels and floating platforms, every link in the chain must function seamlessly. As offshore wind expands into deeper waters and larger turbines, supply chain strength will increasingly decide which regions lead the global offshore wind transition

Ismot Jerin is the founder and Editor-in-Chief of WindNewsToday, an independent publication covering offshore wind, renewable energy policy, and clean power markets with an analytical focus on the United States and global energy transition.